13″x19″ Leather bound 18 page hand assembled book, presented in the group exhibit “The Un(Framed) Photograph” focusing on how the art of photography, the photographic process, and related media are used to convey content, form, text, and image, within a broader context of book arts practices. Curated by Alexander Campos and Doug Beube, at The Center for Book Arts, New York City, July 2011.

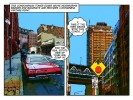

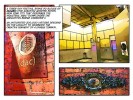

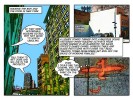

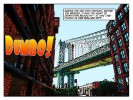

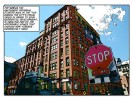

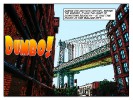

The work is intended to explore the Brooklyn neighborhood of Dumbo, and is part of a series of works using this same material in different formats including video projection and large format prints on paper and canvas. The following are some installation images.

Project Description:

This work takes 30 Washington Street as its starting point, to explore Dumbo’s unique history, and its architectural and sociological development. The artwork, in a form similar to the comic book, take inspiration from the factories built along the East River waterfront.

Dumbo is a place of outsized architecture. Everything is at the scale of elephants or super heroes. In addition to its rich history, it is currently the site of some of the most intense gentrification in New York City. In Dumbo Comic Book the neighborhood and the buildings themselves are characterized through the visual language of the comic book, in order to provoke thought on issues of urban planning, quality of life, and the visual impact of the street level built environment. The project acknowledges the scale of the area and the special place which architecture and development holds here.

Methods:

This work started from 12 megapixel digital stills shot on the streets of Dumbo. These images are then individually run through a variety of different types of desktop printing software and extensively reworked and elaborated, with a focus on the use of algorithms for edge detection, and chromatic separation and simplification, resulting in a set of “Technicolor” schemed cartoon prints, capturing architectural detail, and the street level build environment.

Text has been added by doing a Google search for the word “Dumbo” and culling bits of text and actual quotes from the search results. Part of the byproduct of this method is that elements of text treating the 1941 Walt Disney Animated feature by the same name also make their way into the work, serendipitously adding to critique of issues within the neighborhood.

Working with the form of the comic, this project attempts to provoke thought on issues of urban planing, quality of life, and visual impact of the street level built environment.

For details on other work from this series see:

http://www.paulclay.net/2009/dumbo-comic-print-work-2009/

and:

http://www.paulclay.net/2006/dumbo-comic-2006/

Two works from this series appeared in the group exhibit, “Anthropology: Revisited, Reinvented, Reinterpreted”, at Central Booking, Brooklyn, NY, November 2009. The work is intended to explore the Brooklyn neighborhood of Dumbo, and is available in two forms:

As individual 44″ x 66″, or 22″ x 33″ prints, archival ink, on acid free 100 percent cotton paper.

As individual images without text in the form of 38″ x 54″ archival ink prints on canvas.

Project Description:

Dumbo Comic (Print Work) takes 30 Washington Street as its starting point, to explore Dumbo’s unique history, and its architectural and sociological development. The artworks, in the form of comics, take inspiration from the factories built along the East River waterfront, and from Robert Gair’s position in the end of the 19th century as an inventor involved in industrial printing, cardboard box manufacturing, and real estate.

The work includes reference to the idea of the “Walled City”, a nickname for Brooklyn in the time before the bridges, when there were so many warehouses along the river that it created the look of a walled fortress from the water side. The name can also be interpreted as a reference to the subsequent isolation that Dumbo suffered from, following the construction of the bridges and the Brooklyn Queens Expressway. The bridges and expressway not only made it hard to pass directly into Dumbo from the rest of Brooklyn, but also, because of the length of the exit-ways off of the bridge actually made all the Brooklyn/Manhattan traffic bypass Dumbo, traveling several stories above it. This (at first) tragic walling off, ultimately helped to preserve many of the historic qualities of the neighborhood which are valued today.

Dumbo, New York City’s 90th historic district, is bounded by John Street to the north, York Street to the south, Main Street to the west and Bridge Street to the east, and includes 91 buildings that reflect its industrial heritage. The Brooklyn waterfront region was one of the premier industrial areas in the United States, and at the turn of the 20th century, Brooklyn was the fourth-largest manufacturing center in the country.

Dumbo Comic (Print Work) looks at the historical development of this area through the use of line drawing, and the comic. The line is a simple yet powerful visual tool. Greek legend has it that the first drawing originated from someone using a stick to copy shadows in the sand, and line drawing has long functioned to allow a kind of caricature, or portrait of a person or thing. Comics use a simplified, or iconic visual language to explain complex ideas and narrative structures – a kind of “amplification through simplification”. The form tends to be democratic in nature, and readily accessible to a broad spectrum of society.

The origins of the modern single frame political cartoon can be traced to Britain in the 1800’s and is distinguished by the use of caricature. Throughout much of the United States’ history, political cartoons have held a prominent place. In the Civil War era, Thomas Nast invented the “Donkey” and “Elephant” that remain today the standard signs for the Democratic and Republican parties. They help us focus on the metaphors used in societal discourses.

Comics (or multi-frame cartoons) developed in the late 19th and early 20th century, alongside the similar forms of film and animation. The history and development of comics is directly linked to the development of 19th century manufacturing, to newspapers, and to the re-invention of printing as a large-scale industrial process. Robert Gair was a part of this movement, and the development of serial frame comics was happening at exactly the same time he was building “Gairville” in what is now Dumbo. Further, Gair’s newly developed process of industrial printing on cardboard, and his industrial production system for cardboard boxes was likely inspired by newspaper industrialization. Gair’s former factory was located in Manhattan near the Puck building, an historic area in the development of industrial printing.

Dumbo is a place of outsized architecture. Everything is at the scale of elephants or super heroes. In addition to its rich history, it is currently the site of some of the most intense gentrification in New York City. In Dumbo Comic (Print Work) the neighborhood and the buildings themselves are characterized through the visual language of the comic book, in order to provoke thought on issues of urban planning, quality of life, and the visual impact of the street level built environment. The project acknowledges the scale of the area and the special place which architecture and development holds here.

Methods:

Dumbo Comic (Print Work) consists of two series of works with images starting from 12 megapixel digital stills shot on the streets of Dumbo. These images are then individually run through a variety of different types of desktop printing software and extensively reworked and elaborated, resulting in a set of “Technicolor” schemed cartoon prints, capturing architectural detail, and the street level build environment.

Text has been added by doing a Google search for the word “Dumbo” and culling bits of text and actual quotes from the search results. Part of the byproduct of this method is that elements of text treating the 1941 Walt Disney Animated feature by the same name also make their way into the work, serendipitously adding to critique of issues within the neighborhood.

Working with the form of the comic, this project attempts to provoke thought on issues of urban planing, quality of life, and visual impact of the street level built environment.

Presented at theDumbo Art Center (dac) Art under the bridge festival, Brooklyn, NY, 2006. The work is intended to explore the Brooklyn the neighborhood of dumbo.

Project Description:

Single channel, 18 Frame, 600 x 800 pixel, RGB data projection work

Presented as part of the d.u.m.b.o. arts center (dac) 10th annual art under the bridge festival, 2006. Projected on the blank three story wall in the small parking lot on the South West corner of Jay and Water Street, Dumbo, Brooklyn.

Dumbo is a place of outsized architecture. Everything is at the scale of elephants or super heroes. It is also has a rich history, and is currently the site of some of the most intense gentrification in New York City. This project acknowledges the scale of the area (and the special place which architecture holds here) by working with the structure of the comic book and the giant billboard.

Methods:

All images started out as 12 megapixel digital still images shot on the streets of dumbo, capturing architectural detail, and the street level build environment. Text was added by doing a Google search for the word “dumbo” and culling bits of text and actual quotes from the search results.

By working with the idea of the comic and the billboard, this project attempts to provoke thought on issues of urban planing, quality of life, and visual impact of the street level built environment.

Palace of Contemplation, 5 Sunsets and 5 Dawns, a 20 minute DVD video art work presented at the Cairo Opera House Art Gallery, Cairo, Egypt, uses the concept of the book to explore notions of learning, and uses the image of a book to create a “frame story†which “bookends†the piece. It is a poetic evocation of the Abandoned Halim Palace in Cairo, as well as a meditation on the whole life cycle of the building and its meaning in people’s lives, both throughout its current history, and into envisioned possible futures.

Video Stills:

Video Excerpt:

(Note: The first 49 seconds of the piece are completely silent. Best watched in High Quality – Click video once to play, then after video begins click the “HQ” icon on the lower right. Video will restart in High Quality.)

[tubepress]

Project Description:

In 2005, with the help of friends, I came across an abandoned palace which sits right in the heart of Cairo, in the Ismailia district, a poor neighborhood of auto chop shops and car mechanics.

It was built by Prince Saiid Halim Pasha, a grandson of Mohammed Ali (Wali of Egypt for the Ottoman Empire, and regarded as the “founder of modern Egypt”). Saiid Halim who became the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, built the grand red marble town house for his wife Amina Indji Toussoun, herself a great-granddaughter of Mohammed Ali. History has it that Prince Halim’s father could have been the ruler of all Egypt had it not been for his highly ambitious nephew.

On the first day of Ramadan I was able to arrange a tour of the place. I was taken both by the architecture and by its history, it having been a school first for elites, and in the end for wayward youth, before becoming totally abandoned. Some people had the idea of turning it into a contemporary art museum, but the neighborhood it resides in was beginning to show the signs of gentrification, and others wished to see it torn down or converted to luxury living space.

Several days later I came back with a video camera to document the building with an eye toward creating an artwork, but by this time the mood had already changed. Arriving at the front gates, I was met by guards who informed me that for safety’s sake, no one was allowed to enter. The artwork about this piece of architecture had already begun forming in my mind. Denied access, I decided simply to walk the perimeter and record a single circumambulation of the space.

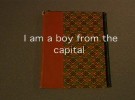

The work uses the concept of the book to explore notions of learning, and uses the image of a book to create a “frame story” which “bookends” the piece. The video begins with the image of a grammar school book from the actual site, and tells the brief story of a boy from the school and the powerful Egyptian ruler who built the palace for his wife. Text about the boy comes not from the book pictured, but rather from an open source wiki book intended to teach Arabic to English speakers, and this same text appears later in the video in Arabic as well.

A little like the 1939 feature film “The Wizard of Oz” in which the “dream sequence” (in color) is the most vivid part, in “Palace…” sound and active movement only occur during the circumambulation stage, representing an imaginary five year journey into the future.

The Buraq was a kind of mythical winged horse and the traditional lightning steed of the prophets for dream journeys. Here in this neighborhood of garages and auto mechanics, the Buraq is replaced by the sound of a mini van starting up at the beginning of the journey, then driving away at the end.

Egypt is primarily Sunni, among whom fasting during Ramadan is considered one of the Five Pillars of Islam: fasting, charity, prayer five times a day, proclamation of faith, and making a pilgrimage to Mecca. “Palace…” involves a kind of pilgrimage around the space, and as Ramadan begins at dawn and ends with sunset, (thus completing the holy month until the following year,) the phrase “Five Sunsets and Five Dawns” actually indicates a passage of five years.

The number five appears in the work in a number of other ways as well, including a hand drawn chart showing the four seasons plus the month of Ramadan, the screen split into quadrants with a full screen layer above, and the overlay in the video of five kinds of language – namely Arabic, English, ancient Egyptian, the language of mathematics, and of symbols drawn by children.

As the journey circling the building begins, the viewer is asked to imagine what the Halim Palace might be, five Ramadans into the future. Montaged over the video documenting the exterior are the drawings charting Ramadan to 2010 as it clocks around the seasons, tracings of actual children’s drawings left behind at the site from the days of the school, mathematical symbols relating to light and learning, as well as parts of an ancient Egyptian tale in hieroglyphics, used to educate scribes. Elements of text in the video are in both English and Arabic, and include common Arabic proverbs relating to the palace, such as “Seek education from the cradle to the grave.”

The sound track is composed of audio from popular radio stations recorded in cabs in downtown Cairo, ambient street noise from the circling walk, and traditional Zar music, an ancient Egyptian ritual healing music, recorded live in a studio on the outskirts of the city.

The piece is a poetic evocation of my personal experience of the physical space, as well as a meditation on the whole life cycle of the building and its meaning in peoples lives, both throughout its current history, and into envisioned possible futures.

The Triumph of Romanticism

A sculptural meditation on the physical nature of books and printing in the contemporary electronic era, composed of fragments of printing plates, document box, pillow, table, flashlight, magnifying glass, and statement. The project description or statement, a part of the artwork itself, is intended to be displayed along with the other elements. It comments both on romanticism generally, and specifically on the very notion of “text” and the idea of “books” in our current digital era. It contains within it a story of the artist in his garret, creating the work as he “begins feverishly to cut the pages one by one…”

24″x36″x36″ at Maxwell Fine Art, Peekskill, New York

Â

Project Description:

“The Triumph of Romanticism” consists of an archival quality lined leather bound document box, a rectangular Indian red silk display pillow of exactly the same dimensions as the box, a chrome and ceramic stand holding a silver flashlight and magnifying glass, a low square traditional oriental table on which all the elements reside, and 58 fragments of hydrophilic offset lithography plates originally used in the printing of an old literary survey book containing a chapter entitled “Triumph of Romanticism.”

The plates were discovered during demo of a 2000 square foot loft in Williamsburg Brooklyn that was being rehabbed. The plates had been used as a building material, forming the ceiling area around a large skylight.

The story seems hardly plausible, but it is entirely true. Picture if you will, the artist in his garret. There is no heat, not even a radiator. There is no electricity. Water is pouring in from around the edges of the skylight above. A shaft of cold winter light bathes the room. In a desperate attempt to discover the source and staunch the flood, and working from instinct rather than reason, the artist begins ripping away the ceiling around the skylight.

Suddenly a discovery is made, on the reverse side of the dingy white metal ceiling flashing is the text of a work. The very ceiling itself – is a book! In his ecstatic and frenzied state, the Sturm und Drang of the artists dreary existence is forgotten. Seizing a pair of tin snips, and drenched in the icy water pouring down around him, the artist begins feverishly to cut the pages one by one from the ceiling.

For the printed work, offset lithography long ago replaced typesetting as the favored method for making books. Today this method itself is being replaced by print-on-demand from ink jet printers, reading on line, and ebooks. Unlike letterpress, offset printing does not involve raised or etched surfaces. Rather, metal plates are chemically treated to retain water in areas that are to be blank space, and reject water but attract grease or oily ink in areas of text. The plates pass the ink to a rubber surface where it is temporarily offset in reverse, and then to the paper. The result not only involves very little wear and thus allows for large print runs, but it also coincidentally means that the shiny text on the surface of the plates is not reversed and thus perfectly legible, just as regular pages in a book.

“The Triumph of Romanticism” evokes both the 19th century love of archiving, and the impression of a lost antiquity displayed in a cabinet of curiosities. The book preserved as ancient or exotic artifact.

This depiction is reenforced by the changes in society relating to text. It is not uncommon for people these days to consider digital text (where the computer understands each character as individually editable) as “actual” text and printed pages as a kind of archaic picture or snapshot, and not the thing itself. The printed page as dumb object, both annoying and of little use. A kind of ghost or residue of the actual text.

Yet this stupid physical object text may soon be all we have left to preserve text with. A host of systems for Digital Rights Management or DRM are being trotted out by corporations attempting to put a strangle hold on the free flow of information caused by the invention of the internet. The argument they make is they are simply trying to protect the copyright so that people can receive just compensation, but the threat to our freedom to read, teach, and preserve books is so great that the American Library Association, in its Office for Information Technology Policy Brief “Digital Rights Management: A Guide for Librarians” outlines at least six key areas of concern where DRM could fundamentally harm the preservation of cultural knowledge for the future. This is because it involves encoding the digital information in such a way that even though you may be in possession of the digital book,the DRM controller decides what and how you can and can not read.

Yet writing is by nature an encoding, and thus always requires some device to decode it – whether a computer program, or simply vision, speech, and language. Cory Doctorow in his brilliant and impressive critique of DRM from the June 17, 2004, “Microsoft Research DRM talk” says “Paper books are the packaging that books come in.” Though he makes light of “how nice a book looks on your bookcase and how nice it smells” and seems almost dismissive of paper books as trash, this statement regarding books and packaging contains a vital notion. The book is the ideas encoded in the text, no matter what form the text is delivered in.

And so we finally circle back around to the book in the ceiling and the artwork made from it. In the electronic text age, here is the supposed “Triumph of Romanticism” – some loose fragments of metal left over from the dark ages of printing. Clearly there is no triumph. This does not constitute the effective preservation of 19th century literature, nor does it solve the problem of how to preserve books, in general, in the face of the overwhelming corporate and national control of media in the coming generation of the electronic age.

In the “The Triumph of Romanticism” the two forgotten art forms of books and found art come together in some kind of pale continued existence. The display, stuck in a maudlin reverence and elegiac longing for the past, strives mightily to achieve its goal, and fails. Yet what is this but a kind of reencoding and presentation of a lost set of ideals – the very essence of romanticism?